Basque Ranching Culture in the Great Basin

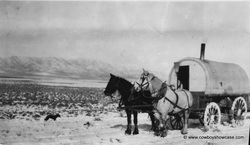

Sheepcamp in the winter

Sheepcamp in the winter

A Century of Immigration

When the Basque herders first arrived in America, sheep herding was a job that required no knowledge of the English language, little formal education, but, for an ambitious man, provided an opportunity to acquire his own band of sheep within a few short years. Back then, one could take sheep in exchange for wages and then head out with a band into the previously unclassified region of the vast Great Basin public lands administered by the US Government. This was all before the US Congress passed the Taylor Grazing Act, which divided and designated livestock grazing allotments on public lands. These early sheep bands were called “tramp sheep outfits.” The new sheep owner sent back to the Basque country for a relative or friend once he became established and the process started all over again. Basque sheep men and Basque herders soon began to appear all over the Great Basin. Thus began an immigration chain that would continue for over a century. Many immigrants knew little of their destination in America. Some knew names, within the Great Basin, such as Elko, Ely, Mountain Home, Jordan Valley, etc. that they had heard before from their relatives or friends that had been to the American west.

Poverty was one reason for young men to leave their homeland. While the Basque sheepherder was near the bottom of the social order in the West in the early 1900s, many men viewed this life as something to be endured temporarily because they would be rewarded with enough saved wages that when they returned to their homeland they could purchase their own business or farm. Another was that the Basques were reluctant to serve France and Spain in their colonial wars. The posting of draft notices often prompted an overnight emigration of young men from the Basque country. Men leaving for this reason sometimes felt they could no longer return to their homeland even when they made enough money in America to do so.

Throughout the American west, “Basque” has been so synonymous with the term “sheepherder” it was assumed that every immigrant from the Basque country had an extensive background in sheep herding. This was not always true. What these young men brought to America was a rural upbringing that gave them some skill in caring for livestock, a hard work ethic, and a willingness to undergo extreme hardship to get ahead in life. It was here in the American west that many of these young men, with instruction from a seasoned sheepherder, learned how to care for sheep.

When the Basque herders first arrived in America, sheep herding was a job that required no knowledge of the English language, little formal education, but, for an ambitious man, provided an opportunity to acquire his own band of sheep within a few short years. Back then, one could take sheep in exchange for wages and then head out with a band into the previously unclassified region of the vast Great Basin public lands administered by the US Government. This was all before the US Congress passed the Taylor Grazing Act, which divided and designated livestock grazing allotments on public lands. These early sheep bands were called “tramp sheep outfits.” The new sheep owner sent back to the Basque country for a relative or friend once he became established and the process started all over again. Basque sheep men and Basque herders soon began to appear all over the Great Basin. Thus began an immigration chain that would continue for over a century. Many immigrants knew little of their destination in America. Some knew names, within the Great Basin, such as Elko, Ely, Mountain Home, Jordan Valley, etc. that they had heard before from their relatives or friends that had been to the American west.

Poverty was one reason for young men to leave their homeland. While the Basque sheepherder was near the bottom of the social order in the West in the early 1900s, many men viewed this life as something to be endured temporarily because they would be rewarded with enough saved wages that when they returned to their homeland they could purchase their own business or farm. Another was that the Basques were reluctant to serve France and Spain in their colonial wars. The posting of draft notices often prompted an overnight emigration of young men from the Basque country. Men leaving for this reason sometimes felt they could no longer return to their homeland even when they made enough money in America to do so.

Throughout the American west, “Basque” has been so synonymous with the term “sheepherder” it was assumed that every immigrant from the Basque country had an extensive background in sheep herding. This was not always true. What these young men brought to America was a rural upbringing that gave them some skill in caring for livestock, a hard work ethic, and a willingness to undergo extreme hardship to get ahead in life. It was here in the American west that many of these young men, with instruction from a seasoned sheepherder, learned how to care for sheep.

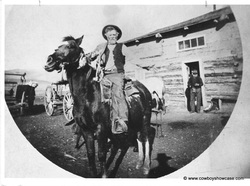

Bernardo Altube and vaquero

Bernardo Altube and vaquero

Basque Stockmen in Northeastern Nevada

By the 1870s, expanded agriculture and overcrowded rangelands in California pushed stockmen beyond the Sierra Mountains into the high desert of the Great Basin. This arid country with its vast rangelands and snow-capped mountains became a magnet for Basque people in America. Coming from a country barely 100 miles across in any direction, Basques, when arriving in the Great Basin, were amazed at the size and emptiness of the land.

Bernardo and Pedro Altube, who were born in the Basque country first settled in San Mateo County and then moved to Palo Alto, California. In 1871, they sold their California ranch, bought 3,000 head of cattle in Old Mexico and trailed these cattle from there to Independence Valley in northwestern Elko County, Nevada. Pedro was reported to have stood six feet six inches tall and was known as Palo Alto, or “Tall Pine.” It is said by some that the town of Palo Alto, California was named after him. Pedro Altube was elected to the Cowboy Hall of Fame at Norman, Oklahoma as Nevada’s candidate in 1960.

The Altube brothers’ ranch, located in Independence Valley, near Tuscarora, was roughly 20 miles long by 10 miles wide with thousands of additional government-owned acres on which they ranged their cattle.

In these early days, the Basque stockmen were cattlemen who brought to Nevada the customs and traditions of the Old California Spanish vaqueros. The customs and traditions that these Basque cattlemen brought could well have been the start of the buckaroo tradition in Nevada, as we know it today.

Range sheep did not begin to arrive in earnest in the Elko County area, in northeastern Nevada, until the beginning of the 1900s when the Altube Brothers, who had started as cattlemen, began to also run large bands of range sheep using Basque herders. The Spanish Ranch, today operated by the Ellison Ranching Company, was part of the vast domain of the Altubes and is still one of the largest ranches in Elko County.

By the 1870s, expanded agriculture and overcrowded rangelands in California pushed stockmen beyond the Sierra Mountains into the high desert of the Great Basin. This arid country with its vast rangelands and snow-capped mountains became a magnet for Basque people in America. Coming from a country barely 100 miles across in any direction, Basques, when arriving in the Great Basin, were amazed at the size and emptiness of the land.

Bernardo and Pedro Altube, who were born in the Basque country first settled in San Mateo County and then moved to Palo Alto, California. In 1871, they sold their California ranch, bought 3,000 head of cattle in Old Mexico and trailed these cattle from there to Independence Valley in northwestern Elko County, Nevada. Pedro was reported to have stood six feet six inches tall and was known as Palo Alto, or “Tall Pine.” It is said by some that the town of Palo Alto, California was named after him. Pedro Altube was elected to the Cowboy Hall of Fame at Norman, Oklahoma as Nevada’s candidate in 1960.

The Altube brothers’ ranch, located in Independence Valley, near Tuscarora, was roughly 20 miles long by 10 miles wide with thousands of additional government-owned acres on which they ranged their cattle.

In these early days, the Basque stockmen were cattlemen who brought to Nevada the customs and traditions of the Old California Spanish vaqueros. The customs and traditions that these Basque cattlemen brought could well have been the start of the buckaroo tradition in Nevada, as we know it today.

Range sheep did not begin to arrive in earnest in the Elko County area, in northeastern Nevada, until the beginning of the 1900s when the Altube Brothers, who had started as cattlemen, began to also run large bands of range sheep using Basque herders. The Spanish Ranch, today operated by the Ellison Ranching Company, was part of the vast domain of the Altubes and is still one of the largest ranches in Elko County.

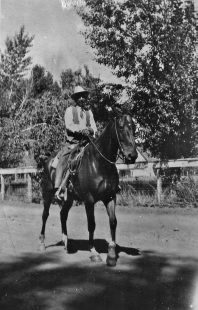

JP Garat

JP Garat

Another Basque livestock family, Jean and Grace Garat reportedly drove their cattle herds over the Sierra Nevada Mountains in 1874 from California into northeastern Nevada and located on the Tuscarora Fork of the Owyhee River. The YP branding iron, first registered in California in 1852 by the Garats, was brought to Nevada and is still used today. This large ranch, started by the Garat’s, is 90 miles Northwest of Elko. It is now owned and operated by the Jackson Family and is called the YP Ranch.

In the annals of western history, there is perhaps an over-fictionalization of the conflicts between sheep and cattle on western ranges. In reality, often both sheep and cattle were run on the same ranch. A good example is the Spanish Ranch in northeastern Nevada where at one time they reportedly ran 18,000 cattle and 12,000 sheep on the same ranch. One reason this was possible is that sheep and cattle do not compete for the same forage. This ranch today still runs both sheep and cattle. Sheep are browsers, eating forbs and brush. Cattle are grass eaters-grazers.

A sheep outfit sells two crops a year, wool fleece and lamb meat. Cow/calf operators only sell calves.

In the annals of western history, there is perhaps an over-fictionalization of the conflicts between sheep and cattle on western ranges. In reality, often both sheep and cattle were run on the same ranch. A good example is the Spanish Ranch in northeastern Nevada where at one time they reportedly ran 18,000 cattle and 12,000 sheep on the same ranch. One reason this was possible is that sheep and cattle do not compete for the same forage. This ranch today still runs both sheep and cattle. Sheep are browsers, eating forbs and brush. Cattle are grass eaters-grazers.

A sheep outfit sells two crops a year, wool fleece and lamb meat. Cow/calf operators only sell calves.

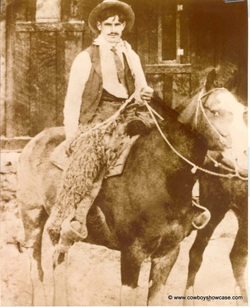

Calisto Laucirica

Calisto Laucirica

Basque Sheepherders

When a young Basque herder arrived in America from half way around the world, he was met by the sheep owner, who many times was a relative. At the main ranch headquarters the young herder was provided with a tent, pack burro or mule, pack saddle and panniers (canvas pack bags), a bedroll of heavy blankets and canvas tarp, Dutch oven for cooking, rifle, canteen, sheep hook and other articles for daily sheep work. A sheep dog completed his outfit, serving as a companion and an essential partner in working sheep on the open range. Many seasoned sheep dogs knew more about herding sheep than the young Basque immigrants.

While the right clothing and equipment could help in getting the young herder to be able to withstand the physical elements of the Great Basin, nothing could prepare these individuals minds for the emptiness and silence of the vast distances that would surround him in his new environment.

When a young Basque herder arrived in America from half way around the world, he was met by the sheep owner, who many times was a relative. At the main ranch headquarters the young herder was provided with a tent, pack burro or mule, pack saddle and panniers (canvas pack bags), a bedroll of heavy blankets and canvas tarp, Dutch oven for cooking, rifle, canteen, sheep hook and other articles for daily sheep work. A sheep dog completed his outfit, serving as a companion and an essential partner in working sheep on the open range. Many seasoned sheep dogs knew more about herding sheep than the young Basque immigrants.

While the right clothing and equipment could help in getting the young herder to be able to withstand the physical elements of the Great Basin, nothing could prepare these individuals minds for the emptiness and silence of the vast distances that would surround him in his new environment.

Photo from Launa Carlson in Gardnerville. The herder is a French Basque but she didn’t recall his name. The area is Big Creek and San Juan Canyon in the Toiyabe Mountains south of Austin, NV. Date is August 1982.

Photo from Launa Carlson in Gardnerville. The herder is a French Basque but she didn’t recall his name. The area is Big Creek and San Juan Canyon in the Toiyabe Mountains south of Austin, NV. Date is August 1982.

STRENGTH TO SURVIVE:

These Basques were tough, hardy individuals but their loneliness and the vast empty country made for a difficult adjustment. There were those who were overwhelmed by the strange country and loneliness, and became victims of a condition the Basque referred to as “txamisuek jota,” or “struck by sagebrush.” They became very reclusive and did not wish to meet or speak with strangers. Most of the herders, however, adapted to their new life in America.

Basque herders were some of the very best sheepherders in western range sheep operations. These men soon found out upon arriving in the American west, that they had entered one of the loneliest professions in the world. Herding sheep in the least populated region of the United States placed these men in a situation, which at times, bordered on total social isolation. However, most Basque men endured the isolation. Basques came from a mountainous country in Spain growing up in rough mountain terrain and an agrarian society. They understood the land and the animals. Hard work was nothing new to Basques. They were real stockmen. They were very dependable and could be counted upon to stay for long periods alone and not leave their flocks.

It is an art form to handle range sheep alone with no fence and no night corrals. The herders had to constantly guard against predators such as mountain lions, bobcats, coyotes and bears, and had to keep moving the band to fresh water and grazing. Efficient management of a band of range sheep demanded total teamwork between the herder and his animals. Herders were careful not to use their dogs too much on their sheep herd. The term, “dogged sheep,” meant the sheep became nervous from overusing a dog on them and their weight would start to fall off. The goal was to produce heavy lambs for sale at shipping time in the fall. Border Collies and Australian Shepherd dogs were the two breeds that were preferred by most by the herders.

Cattle need to be fenced in or handled by a crew of cowboys on horseback, where as one experienced sheepherder would handle 1,000 to 1,200 head of sheep outside relying only on himself, his horse and dogs.

These Basques were tough, hardy individuals but their loneliness and the vast empty country made for a difficult adjustment. There were those who were overwhelmed by the strange country and loneliness, and became victims of a condition the Basque referred to as “txamisuek jota,” or “struck by sagebrush.” They became very reclusive and did not wish to meet or speak with strangers. Most of the herders, however, adapted to their new life in America.

Basque herders were some of the very best sheepherders in western range sheep operations. These men soon found out upon arriving in the American west, that they had entered one of the loneliest professions in the world. Herding sheep in the least populated region of the United States placed these men in a situation, which at times, bordered on total social isolation. However, most Basque men endured the isolation. Basques came from a mountainous country in Spain growing up in rough mountain terrain and an agrarian society. They understood the land and the animals. Hard work was nothing new to Basques. They were real stockmen. They were very dependable and could be counted upon to stay for long periods alone and not leave their flocks.

It is an art form to handle range sheep alone with no fence and no night corrals. The herders had to constantly guard against predators such as mountain lions, bobcats, coyotes and bears, and had to keep moving the band to fresh water and grazing. Efficient management of a band of range sheep demanded total teamwork between the herder and his animals. Herders were careful not to use their dogs too much on their sheep herd. The term, “dogged sheep,” meant the sheep became nervous from overusing a dog on them and their weight would start to fall off. The goal was to produce heavy lambs for sale at shipping time in the fall. Border Collies and Australian Shepherd dogs were the two breeds that were preferred by most by the herders.

Cattle need to be fenced in or handled by a crew of cowboys on horseback, where as one experienced sheepherder would handle 1,000 to 1,200 head of sheep outside relying only on himself, his horse and dogs.

Eustaquio Murubarria,

Nicolas Fagoaga,

Jose “Chapo” Leniz

Eustaquio Murubarria,

Nicolas Fagoaga,

Jose “Chapo” Leniz

From the herder’s point of view

In a personal interview with three former Basque sheep herders, Nicolas Fagoaga, center in this photo, said this about his early years in the sheep business: “I came to Nevada from Basque Country in 1951. I had no experience in handling sheep; I was a cabinetmaker. My brother talked me into coming to America. They sent me into the Ruby Mountains with a pack burro and a tent to work for a sheep man by the name of Tony Smith. My first camp was in a place called Rattlesnake Canyon, near Lee, Nevada. I hated the Rubies. They were rough, steep, and very dangerous. I did not like to be alone. The camp tender would come to my camp every five days. If I was out with my sheep, he left the groceries near my camp and went on. I lasted 4 months. My brother said ‘Stick it out you will become used to it.’ I told him, no, I was leaving for California.

I went to work on a ranch out of Dixon, California. I helped take care of the sheep on the ranch, there were other people around, and we ate our meals as a family. I liked this much better, although it was much harder work than sheep herding in the Ruby Mountains. I stayed with the sheep business for five years, then came back to Elko and started a construction business. Sheep herding in the Rubies was not for me.” Nick is now retired from his construction company and lives in Elko.

Many Basque herders called the Ruby Mountains in Elko County, Nevada “mata hombres” which, in Spanish, means “man killers.”

Jose “Chapo” Leniz (right in the photo and now diseased) also talked about his sheep herding experience. “I came to America in 1954 and first went to work in the Jarbidge Mountains in Northeastern Nevada for sheep man Pete Elia. I lived in a tent, packed a burro, and walked to my sheep. I did this for three years. Then I came to the” Rubies” and went to work for the Sorenson Sheep outfit. They promoted me to camp tender because I had learned a little English and some of the ways of sheep. I took care of six summer bands.” (A summer band is a herd of sheep comprised of 1,000 to 1,200 ewes with their lambs and cared for by one herder and his dogs.) “One day a week I baked the bread for these herders.” (The bread was baked in Dutch ovens, buried in the coals from sagebrush or aspen wood fires.) “I rode a horse and packed the supplies for each herder on pack mules. I visited each herder every five days, which meant there were no days off. Our main camp was in Secret Pass between the East Humboldt Range and the Ruby Mountains. I enjoyed the mountains and the life of a camp tender.” After his herding career “Chapo” retired and lived in Elko for several years.

Eustaquio Murubarria, (left in the photo) who worked for sheep man Paul Enchauspe out of Austin, Nevada in the Toiyobe Mountains for 25 years, talked about his life as a sheepherder. “I went to work as a sheep herder for Paul in 1957 and stayed at it for 25 years, 18 of these were spent sheep herding and then I moved to Paul’s main ranch and took care of his cows, horses and sheep. I herded sheep year around for 18 years. In the winter, we would take our bands south into the desert in the Ione and Gabbs country. I stayed alone most of the time and it did not bother me. After 25 years herding sheep and ranch work I moved to Elko and got out of the sheep business. I was glad to be in town and around some people. I now work for the Elko School District as a custodian and own a home in Elko.”

In a personal interview with three former Basque sheep herders, Nicolas Fagoaga, center in this photo, said this about his early years in the sheep business: “I came to Nevada from Basque Country in 1951. I had no experience in handling sheep; I was a cabinetmaker. My brother talked me into coming to America. They sent me into the Ruby Mountains with a pack burro and a tent to work for a sheep man by the name of Tony Smith. My first camp was in a place called Rattlesnake Canyon, near Lee, Nevada. I hated the Rubies. They were rough, steep, and very dangerous. I did not like to be alone. The camp tender would come to my camp every five days. If I was out with my sheep, he left the groceries near my camp and went on. I lasted 4 months. My brother said ‘Stick it out you will become used to it.’ I told him, no, I was leaving for California.

I went to work on a ranch out of Dixon, California. I helped take care of the sheep on the ranch, there were other people around, and we ate our meals as a family. I liked this much better, although it was much harder work than sheep herding in the Ruby Mountains. I stayed with the sheep business for five years, then came back to Elko and started a construction business. Sheep herding in the Rubies was not for me.” Nick is now retired from his construction company and lives in Elko.

Many Basque herders called the Ruby Mountains in Elko County, Nevada “mata hombres” which, in Spanish, means “man killers.”

Jose “Chapo” Leniz (right in the photo and now diseased) also talked about his sheep herding experience. “I came to America in 1954 and first went to work in the Jarbidge Mountains in Northeastern Nevada for sheep man Pete Elia. I lived in a tent, packed a burro, and walked to my sheep. I did this for three years. Then I came to the” Rubies” and went to work for the Sorenson Sheep outfit. They promoted me to camp tender because I had learned a little English and some of the ways of sheep. I took care of six summer bands.” (A summer band is a herd of sheep comprised of 1,000 to 1,200 ewes with their lambs and cared for by one herder and his dogs.) “One day a week I baked the bread for these herders.” (The bread was baked in Dutch ovens, buried in the coals from sagebrush or aspen wood fires.) “I rode a horse and packed the supplies for each herder on pack mules. I visited each herder every five days, which meant there were no days off. Our main camp was in Secret Pass between the East Humboldt Range and the Ruby Mountains. I enjoyed the mountains and the life of a camp tender.” After his herding career “Chapo” retired and lived in Elko for several years.

Eustaquio Murubarria, (left in the photo) who worked for sheep man Paul Enchauspe out of Austin, Nevada in the Toiyobe Mountains for 25 years, talked about his life as a sheepherder. “I went to work as a sheep herder for Paul in 1957 and stayed at it for 25 years, 18 of these were spent sheep herding and then I moved to Paul’s main ranch and took care of his cows, horses and sheep. I herded sheep year around for 18 years. In the winter, we would take our bands south into the desert in the Ione and Gabbs country. I stayed alone most of the time and it did not bother me. After 25 years herding sheep and ranch work I moved to Elko and got out of the sheep business. I was glad to be in town and around some people. I now work for the Elko School District as a custodian and own a home in Elko.”

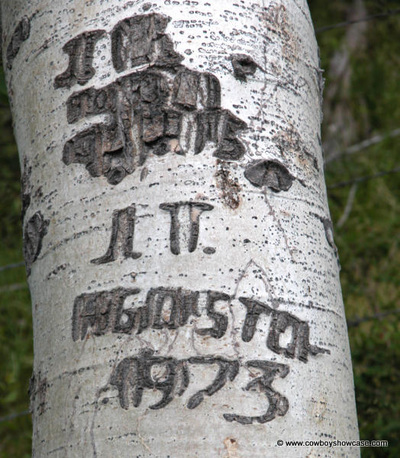

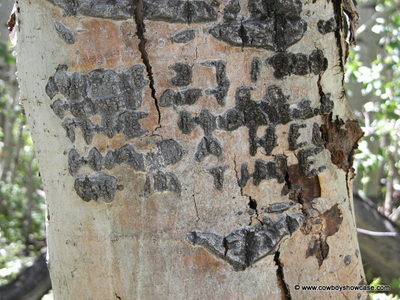

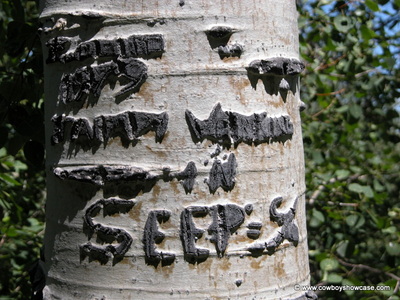

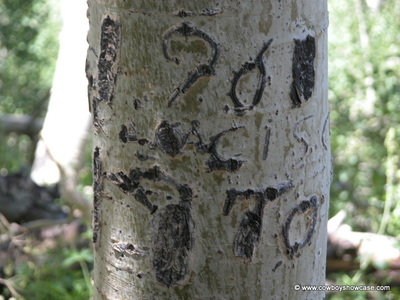

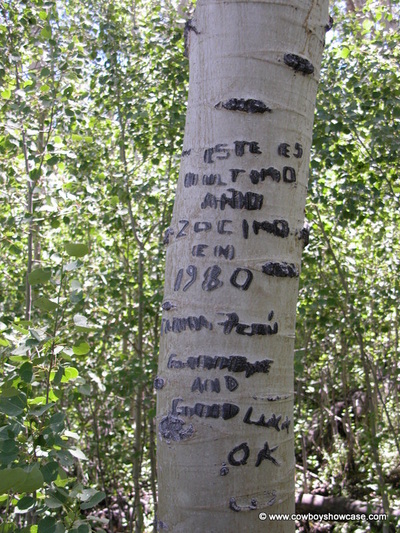

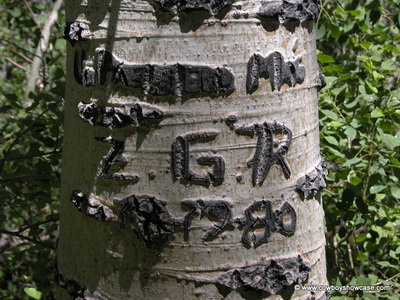

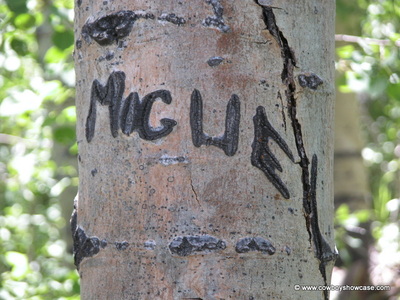

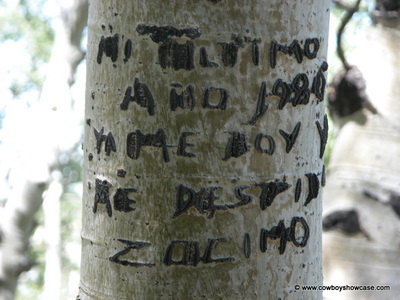

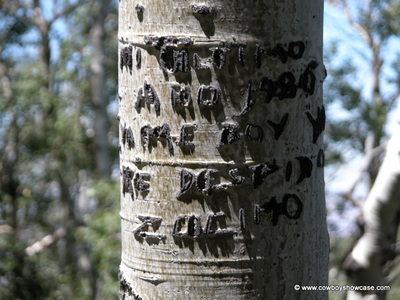

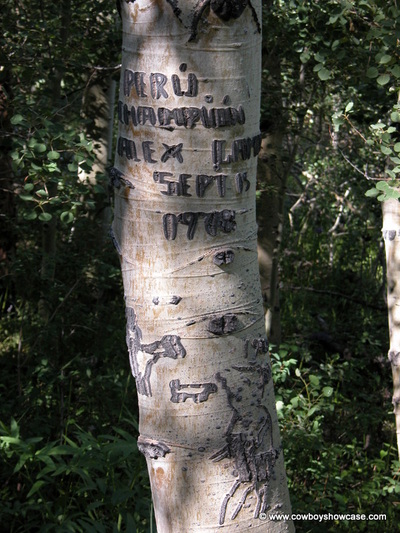

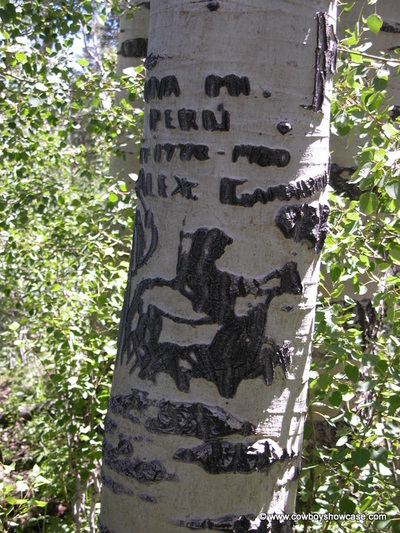

Basque Tree Carvings (“Arborglyphs”)

In the remote mountains of the west, during the summer months, sheepherders camped alone in tents with a pack outfit, horse or pack burro, and their dogs to tend their flocks. Camp tenders, with a pack string, visited the herder about once a week bringing groceries and other necessities. Many times this camp tender was the only other person the herder would see during the entire summer.

A portion of the history of Basque herders has been recorded on aspen trees throughout the mountains of the Great Basin. Solitary during their time in mountains for 4-5 months during the summer, seeing only the camp tenders once a week, herders used tree carving to alleviate boredom and loneliness and record events of note. These herders moved into a rhythm with their sheep and their daily movements. They wanted to leave their mark on the landscape and carved a record of their presence on the bark of aspen trees with a knife or other sharp object for other sheepherders to see. Black scar tissue builds up on the tree’s white bark. As the tree continues to grow vertical scratch lines widen more than horizontal ones, causing a unique tree carving style.

Some of the earliest tree carvings made by Basque herders found and recorded date back to 1895. There is no known tradition of tree carvings found in the Basque Country. With no record of this carving technique being passed from one sheepherder to another in the Basque country, it is assumed that the sheepherder artists in America simply saw the work of past herders who had camped in the same location and added their own tree drawings.

These carvings provide a glimpse into the herders’ idle moments away from their sheep. Most frequently, the carvings were only a name and date and may include the name of their hometown or province in the Basque country. Occasionally there are drawings of women, animals, or objects. Some herders left messages telling where they were going or where they had been, what had happened that day, or where the best feed and water was, etc. Carvings provide a valuable tool for historians because they marked the herder’s whereabouts and movement of their sheep bands.

A large gallery of arborglyph photos is at the bottom of this page.

The Basque Studies Program, Desert Research Institute, University of Nevada in Reno, Nevada, has done several scientific studies of these tree carvings, called “arborglyphs.” http://basque.unr.edu/

Another mark upon the landscape made by the Basque herders were stone cairns called “harrimutilak’ or stone boys. These piles of stone were built to mark their routes and to pass the herder’s time. Many stone boys can still be seen today in the mountains and high deserts of the Great Basin.

In the remote mountains of the west, during the summer months, sheepherders camped alone in tents with a pack outfit, horse or pack burro, and their dogs to tend their flocks. Camp tenders, with a pack string, visited the herder about once a week bringing groceries and other necessities. Many times this camp tender was the only other person the herder would see during the entire summer.

A portion of the history of Basque herders has been recorded on aspen trees throughout the mountains of the Great Basin. Solitary during their time in mountains for 4-5 months during the summer, seeing only the camp tenders once a week, herders used tree carving to alleviate boredom and loneliness and record events of note. These herders moved into a rhythm with their sheep and their daily movements. They wanted to leave their mark on the landscape and carved a record of their presence on the bark of aspen trees with a knife or other sharp object for other sheepherders to see. Black scar tissue builds up on the tree’s white bark. As the tree continues to grow vertical scratch lines widen more than horizontal ones, causing a unique tree carving style.

Some of the earliest tree carvings made by Basque herders found and recorded date back to 1895. There is no known tradition of tree carvings found in the Basque Country. With no record of this carving technique being passed from one sheepherder to another in the Basque country, it is assumed that the sheepherder artists in America simply saw the work of past herders who had camped in the same location and added their own tree drawings.

These carvings provide a glimpse into the herders’ idle moments away from their sheep. Most frequently, the carvings were only a name and date and may include the name of their hometown or province in the Basque country. Occasionally there are drawings of women, animals, or objects. Some herders left messages telling where they were going or where they had been, what had happened that day, or where the best feed and water was, etc. Carvings provide a valuable tool for historians because they marked the herder’s whereabouts and movement of their sheep bands.

A large gallery of arborglyph photos is at the bottom of this page.

The Basque Studies Program, Desert Research Institute, University of Nevada in Reno, Nevada, has done several scientific studies of these tree carvings, called “arborglyphs.” http://basque.unr.edu/

Another mark upon the landscape made by the Basque herders were stone cairns called “harrimutilak’ or stone boys. These piles of stone were built to mark their routes and to pass the herder’s time. Many stone boys can still be seen today in the mountains and high deserts of the Great Basin.

Seasons of The Herders:

The daily and seasonal routines of sheepherders in a range sheep operation varied little throughout the Great Basin. Each cycle began by driving the sheep to spring lambing grounds. The ewes were sheared (the wool fleece shaved off) after the birth of the lambs. The lambing grounds were chosen for the protection they afforded from the prevailing winds and for plentiful grass and water. Some sheep outfits built wooden buildings called” lambing sheds” to protect the newborn lambs from the elements. After all the lambs were born, they were processed. Male lambs were castrated; all the lamb’s tails were “docked” (bobbed) for cleanliness, the lambs were ear marked, and the ewes and lambs were marked with paint using the owner’s brand.

After lambing, the herders set off on the trail with their ewes and lambs headed for the mountains, moving up from the sagebrush flats, through juniper foothills, into the aspen–lined creeks of the mountains for the summer. All these movements were made slowly because the herd grazes its way along the trail. Ten to twelve miles in a day would be a big day trailing sheep.

During the hot summer months of July and August, sheep would leave their bed ground on an open hillside where they had spent the night around sunup and began to graze; the herder would leave his camp long before daylight to check on his band. Black sheep were used as markers, and the herder would count the blacks. If they were all with the band, chances are all of the sheep were together. If a black sheep was missing then the herder and his dogs would set out in search of the missing black sheep and whatever other sheep had gone with this marker. Bells placed around the neck of some older ewes (female sheep) were also used to help keep track of the band. The sheep would graze down hill to water, drink their fill, and then shade up, and rest during the heat of the day until around 4:00pm. Then they would get up and start to graze uphill until dark. The herder and his dogs would position the band on an open hillside for the night, then head for his tent in the dark or stay with his band in his bedroll with his rifle and dogs if coyotes or mountain lions were killing his sheep. This was a 7-day a week job. Sheep do not take days off in their daily movements. Sheep were moved to fresh grazing every day or two. Salt was also used to help move sheep around.

Fall comes early in the high country. Aspens start to turn color in late August and heavy frost lines the meadow bottoms in early mornings. At this time, the herders would point their bands back down out of the mountains towards the lower desert. Generally, two summer bands would merge and aging ewes and lambs were sorted off and sent to market. With the size of the bands reduced, some of the herders would go to town to spend the winter. The remaining herders would head their bands toward the winter range, which was, sometimes, hundreds of miles from the summer range. On the trip to the winter range and during the winter months, the herders lived in sheepwagons. The sheepwagon, a forerunner of the modern travel trailer, is a camp on wheels with beds, a table, and a wood stove. It was pulled, in the old days, by a team of horses and later by a pickup. During this time, two herders sometimes would share a camp. One would drive the team or pickup pulling the sheep camp; the other would ride his horse and move the sheep, with the help of his dogs, down the trail.

Elko County, at one time when there were over a million sheep in Nevada, had the largest concentration of Basque sheepherders in the United States. Basque herders began to be brought to America on contracts set up by the Western Range Association and the U. S. Immigration Service. The herders came to work on sheep contracts stipulating they must work with sheep for 3 years once they reached the United States and then return to their homeland. Sometimes they would sign up to come back for a second or third tour. In the early years, before strict immigration laws were enacted, many herders came, stayed in the United States, and obtained American citizenship and became sheep owners and businessmen.

The daily and seasonal routines of sheepherders in a range sheep operation varied little throughout the Great Basin. Each cycle began by driving the sheep to spring lambing grounds. The ewes were sheared (the wool fleece shaved off) after the birth of the lambs. The lambing grounds were chosen for the protection they afforded from the prevailing winds and for plentiful grass and water. Some sheep outfits built wooden buildings called” lambing sheds” to protect the newborn lambs from the elements. After all the lambs were born, they were processed. Male lambs were castrated; all the lamb’s tails were “docked” (bobbed) for cleanliness, the lambs were ear marked, and the ewes and lambs were marked with paint using the owner’s brand.

After lambing, the herders set off on the trail with their ewes and lambs headed for the mountains, moving up from the sagebrush flats, through juniper foothills, into the aspen–lined creeks of the mountains for the summer. All these movements were made slowly because the herd grazes its way along the trail. Ten to twelve miles in a day would be a big day trailing sheep.

During the hot summer months of July and August, sheep would leave their bed ground on an open hillside where they had spent the night around sunup and began to graze; the herder would leave his camp long before daylight to check on his band. Black sheep were used as markers, and the herder would count the blacks. If they were all with the band, chances are all of the sheep were together. If a black sheep was missing then the herder and his dogs would set out in search of the missing black sheep and whatever other sheep had gone with this marker. Bells placed around the neck of some older ewes (female sheep) were also used to help keep track of the band. The sheep would graze down hill to water, drink their fill, and then shade up, and rest during the heat of the day until around 4:00pm. Then they would get up and start to graze uphill until dark. The herder and his dogs would position the band on an open hillside for the night, then head for his tent in the dark or stay with his band in his bedroll with his rifle and dogs if coyotes or mountain lions were killing his sheep. This was a 7-day a week job. Sheep do not take days off in their daily movements. Sheep were moved to fresh grazing every day or two. Salt was also used to help move sheep around.

Fall comes early in the high country. Aspens start to turn color in late August and heavy frost lines the meadow bottoms in early mornings. At this time, the herders would point their bands back down out of the mountains towards the lower desert. Generally, two summer bands would merge and aging ewes and lambs were sorted off and sent to market. With the size of the bands reduced, some of the herders would go to town to spend the winter. The remaining herders would head their bands toward the winter range, which was, sometimes, hundreds of miles from the summer range. On the trip to the winter range and during the winter months, the herders lived in sheepwagons. The sheepwagon, a forerunner of the modern travel trailer, is a camp on wheels with beds, a table, and a wood stove. It was pulled, in the old days, by a team of horses and later by a pickup. During this time, two herders sometimes would share a camp. One would drive the team or pickup pulling the sheep camp; the other would ride his horse and move the sheep, with the help of his dogs, down the trail.

Elko County, at one time when there were over a million sheep in Nevada, had the largest concentration of Basque sheepherders in the United States. Basque herders began to be brought to America on contracts set up by the Western Range Association and the U. S. Immigration Service. The herders came to work on sheep contracts stipulating they must work with sheep for 3 years once they reached the United States and then return to their homeland. Sometimes they would sign up to come back for a second or third tour. In the early years, before strict immigration laws were enacted, many herders came, stayed in the United States, and obtained American citizenship and became sheep owners and businessmen.

Basque Hotels:

Several Basque hotels still operate in towns throughout Nevada. One of these hotels is the Star in Elko. The 22-room hotel built in 1910 provided a winter home for sheepherders. It was the meeting and resting place for Basque herders who had no other home and still serves as a home for retired Basque herders. There are three other fine Basque restaurants in Elko, Toki Ona, The Nevada, and Biltoki. Basque food and drink are a popular specialty of the Great Basin region. Meals are served family style as they always have been, both to residents and the appreciative public.

Current Range Sheep Industry

Today most of the sheep on the open range are gone as are their Basque herders. Most contemporary contract sheepherders today come from South American countries, primarily Peru and Chile. In 1973, when I came to Elko, there were approximately 100,000 head of sheep in the Ruby Mountains on their summer range. In 10 to 12 years, most sheep outfits and their Basque herders were gone. Some reasons for the demise of the range sheep industry in Nevada were government regulations including Nevada Department of Wildlife and Nevada Big Horns Unlimited sportsman's organization wishing to remove Domestic Sheep from Nevada range lands and replace them with wild Desert, California and Rocky Mountain Big Horn sheep. Also falling lamb and wool prices and increased imports, predators, changes in Federal livestock land practices, labor problems, etc. added to the range sheep demise.

I had the opportunity to work with and camp with many fine Basque herders who would greet you and feed you and your horses and dogs when you rode into their camp. I feel very fortunate to have known, eaten, and camped with many of these men. I salute these Basque herders!

Today, Basques continue to play a significant role in the region’s livestock industry. Many of the children and grandchildren of the Basque sheep men who endured the Great Depression and enjoyed the prosperity of the war years are successful cattle ranchers throughout the Great Basin.

Today most of the sheep on the open range are gone as are their Basque herders. Most contemporary contract sheepherders today come from South American countries, primarily Peru and Chile. In 1973, when I came to Elko, there were approximately 100,000 head of sheep in the Ruby Mountains on their summer range. In 10 to 12 years, most sheep outfits and their Basque herders were gone. Some reasons for the demise of the range sheep industry in Nevada were government regulations including Nevada Department of Wildlife and Nevada Big Horns Unlimited sportsman's organization wishing to remove Domestic Sheep from Nevada range lands and replace them with wild Desert, California and Rocky Mountain Big Horn sheep. Also falling lamb and wool prices and increased imports, predators, changes in Federal livestock land practices, labor problems, etc. added to the range sheep demise.

I had the opportunity to work with and camp with many fine Basque herders who would greet you and feed you and your horses and dogs when you rode into their camp. I feel very fortunate to have known, eaten, and camped with many of these men. I salute these Basque herders!

Today, Basques continue to play a significant role in the region’s livestock industry. Many of the children and grandchildren of the Basque sheep men who endured the Great Depression and enjoyed the prosperity of the war years are successful cattle ranchers throughout the Great Basin.

Joe Anacabe

Joe Anacabe

Basque Descendants in the United States

Descendants of the early Basque herders still live throughout the west, especially in California, Idaho, Oregon, Wyoming, Washington, and Nevada. One of these descendants, Anita Anacabe, carries on a business in Elko, Nevada called Elko General Merchandise. The business was started by her father Jose (Joe) Anacabe, a former, buckaroo, stagecoach driver and sheepherder. Over 70 years later, this store still provides stockmen, miners, and others with quality boots, coats, hats, and other outdoor gear.

Descendants of the early Basque herders still live throughout the west, especially in California, Idaho, Oregon, Wyoming, Washington, and Nevada. One of these descendants, Anita Anacabe, carries on a business in Elko, Nevada called Elko General Merchandise. The business was started by her father Jose (Joe) Anacabe, a former, buckaroo, stagecoach driver and sheepherder. Over 70 years later, this store still provides stockmen, miners, and others with quality boots, coats, hats, and other outdoor gear.

The National Basque Festival

The main center of the Basque culture in Nevada is Elko. Basque descendants continue to carry on traditions of their homeland, including customs, language, dances, dress, and food. Basque people are very proud of their cultural heritage and each year since 1964 Elko has been host to a summer festival. This festival, held annually the first weekend in July, is now proclaimed the National Basque Festival. Destination Magazine listed the Festival among its “ Top 100 Events in North America.”

What can you expect to experience at the National Basque Festival?

People come from all over the world to take part in these festivities. Many times, Catholic priests, woodchoppers and weight lifters from the Pyrenees Mountains in the Basque country have been invited to participate in this festival.

The games that you will see all originated in the Basque Country years ago. The clearing of fields and forests became a contest between Basque men to see who could carry the biggest rock or chop the most wood. The dances were part of celebrations for a people who wished to express in dance their zest for life. These dances have a great history and symbolize everyday activities that fisherman and farmers do in the Basque country. These games and dances have been handed down for generations and continue to this day.

The main center of the Basque culture in Nevada is Elko. Basque descendants continue to carry on traditions of their homeland, including customs, language, dances, dress, and food. Basque people are very proud of their cultural heritage and each year since 1964 Elko has been host to a summer festival. This festival, held annually the first weekend in July, is now proclaimed the National Basque Festival. Destination Magazine listed the Festival among its “ Top 100 Events in North America.”

What can you expect to experience at the National Basque Festival?

People come from all over the world to take part in these festivities. Many times, Catholic priests, woodchoppers and weight lifters from the Pyrenees Mountains in the Basque country have been invited to participate in this festival.

The games that you will see all originated in the Basque Country years ago. The clearing of fields and forests became a contest between Basque men to see who could carry the biggest rock or chop the most wood. The dances were part of celebrations for a people who wished to express in dance their zest for life. These dances have a great history and symbolize everyday activities that fisherman and farmers do in the Basque country. These games and dances have been handed down for generations and continue to this day.

Running From the Bulls

In the year 2000, in order to increase interest and attendance in the National Basque Festival, Anna Urrizaga and the Elko Festival committee made arrangements to bring Mexican fighting bulls from Idaho to put on a “Running From the Bulls” similar to the popular “Running of the Bulls” held in Pamplona, Spain.

Portable fence panels are installed to establish a confined running course on almost two blocks of the streets of downtown Elko. Bulls are confined in a stock trailer on one end of the course. Contestants, who must be 18 or older, sober, and sign a liability release, run ahead of the bulls to a confinement pen at the other end of the course. Runners are encouraged to wear white shirts and pants, and wear red scarves and a sash in the traditional Basque way.

This was a very popular event with an estimated 5,000 spectators. Obviously this event has its problems with logistics and in 2013 it will not be held. Hopefully it will reappear.

If you want to witness a proud people, carrying on their heritage and traditions and passing it along to their children visit Elko, Nevada the first weekend in July and “become Basque for a weekend.”

We wish to thank the Northeastern Nevada Museum, Jan Peterson, and Anita Anacabe-Franzoiaoury, Anacabe’s Elko General Merchandise, for access to photographs and research materials. We also wish to thank Catalina Laughlin for arranging personal interviews and interpreting with former Basque sheepherders.

In the year 2000, in order to increase interest and attendance in the National Basque Festival, Anna Urrizaga and the Elko Festival committee made arrangements to bring Mexican fighting bulls from Idaho to put on a “Running From the Bulls” similar to the popular “Running of the Bulls” held in Pamplona, Spain.

Portable fence panels are installed to establish a confined running course on almost two blocks of the streets of downtown Elko. Bulls are confined in a stock trailer on one end of the course. Contestants, who must be 18 or older, sober, and sign a liability release, run ahead of the bulls to a confinement pen at the other end of the course. Runners are encouraged to wear white shirts and pants, and wear red scarves and a sash in the traditional Basque way.

This was a very popular event with an estimated 5,000 spectators. Obviously this event has its problems with logistics and in 2013 it will not be held. Hopefully it will reappear.

If you want to witness a proud people, carrying on their heritage and traditions and passing it along to their children visit Elko, Nevada the first weekend in July and “become Basque for a weekend.”

We wish to thank the Northeastern Nevada Museum, Jan Peterson, and Anita Anacabe-Franzoiaoury, Anacabe’s Elko General Merchandise, for access to photographs and research materials. We also wish to thank Catalina Laughlin for arranging personal interviews and interpreting with former Basque sheepherders.

Events

- Running from the Bulls was held for several years. Was discontinued in 2013.

- Basque traditional dancing in authentic costumes

- Weightlifting

- Wood chopping

- Basque Relay Race

- Handball (pelota) tournament

- Basque Picnic and Barbeque with games, dancing, music, food

- Golf tournament

- Interactive living history programs

- Sheepherder’s Bread Baking Contest

- Outdoor Catholic Holy Mass

Contact Information:

Elko Jaietan

Elko Basque Club

PO Box 1321

Elko, NV 89803

775-738-9957

Article by Mike Laughlin

Photos by Lee Raine

Vintage black and white photos courtesy of Northeastern Nevada Museum

Elko Jaietan

Elko Basque Club

PO Box 1321

Elko, NV 89803

775-738-9957

Article by Mike Laughlin

Photos by Lee Raine

Vintage black and white photos courtesy of Northeastern Nevada Museum