"Orphan Boy" -

excerpt from a book by R.J. Milne.

|

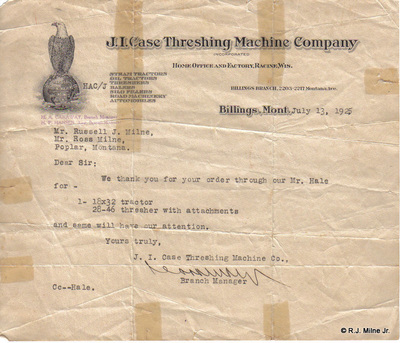

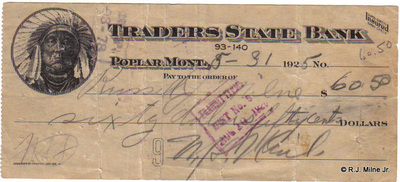

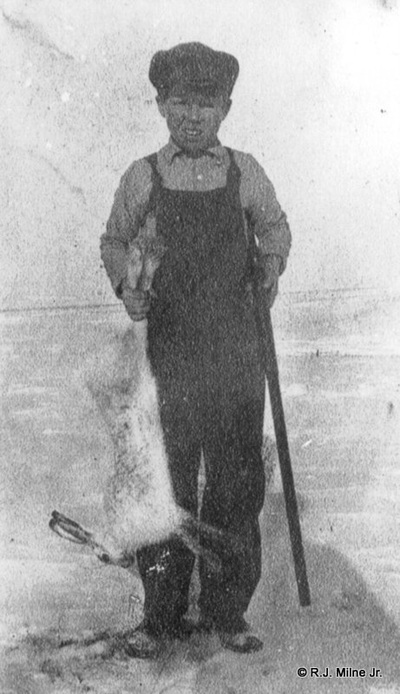

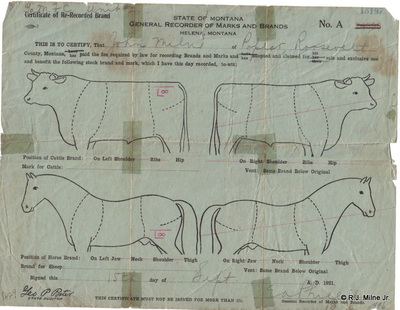

I published my dad's story about his life as an orphan. At the age of eleven (1915) Russell was put on a train from Indiana to Montana, where he worked numerous farms and ranches. Title: "Orphan Boy" by R. J. Milne, Jr. - Amazon Attached photos of Russell in Poplar, Montana - 1915, branding certificate issued to him at seventeen, his threshing machine order and check received from a part-time farmer and home brewer he worked for. Thank you, Russell. J Milne, Jr. Excerpts taken from the book below photos:

Click on photos for larger views. Uncle Jim’s homestead consisted of three hundred and sixty acres, most of which was grazing land. He and nearly all the Milne homesteaders were settled south of the Missouri River, between Poplar and Ritchey. The majority of the area was farmland, except for every other section, which was given to the railroad where they laid track, and every fifth section, which was school property. Uncle Jim acquired his homestead by building a house on the land and living there three years, cultivating the soil. Then he, along with three witnesses, went before the land commission, receiving a deed signed by the President of the United States. Property taxes were appraised at fifteen dollars per half-section. Many farmers didn’t have enough money, so the government let them work it out. The government gave every Indian child that was born three hundred and twenty acres of land, even if fathered by a white man. Most of them wouldn’t develop their property, so the law was later changed to giving them money, instead. The administration also tried educating Indian children and made them live at the school. A few old-timers didn’t like that; at night, they tied saddled horses outside, so that the young ones could leave. However, some Indians did become well educated.

Uncle Jim and Aunt Pansy were very poor; their earnings were around three hundred dollars a year. We had little to eat; nevertheless, it was the first time in my life that I was happy. They treated me well. Uncle Jim tried raising wheat. He slaved hard all day, plowing, but the ground was very hard, dry, and didn’t yield much. When he stopped to rest, his horses laid down in the field, from lack of food; they were nothing but skin and bones. All homesteaders worked long hours, only to barely make a living. Water, food, and equipment were scarce out there. Water for drinking and cooking had to be hauled in barrels from three miles away, and put on the shady side of the house. When Uncle Jim needed a new wagon and couldn’t afford one, he’d hitch a team to a flat board, nailed to sleigh-like runners. These makeshift wagons were used in winter or summer. Away we’d go—with Uncle Jim always laughing, regardless of hard times. I worked on Uncle Jim’s granary, hunted jackrabbits and prairie chickens in winter and summer for food, and sometimes to earn money. We dug our own coal from the badlands, and later I helped dig a well, so that we didn’t have to haul water. I attended Hillcrest School, four miles away; I didn’t have a horse, so I walked. In winter, I trudged through bitter cold and snow. The teacher lived in the little one-room schoolhouse, and earned about sixty-five dollars a month. The cabin wasn’t just a place for children to learn. It was also used for church, meeting places, weddings, and other activities. When dances were held, women brought sandwiches and cakes; men paid a dollar, and the party usually lasted until morning. During these events, the boys stuck together; you were considered a sissy if you hung out with girls. For fun, we boys went swimming in Red Water—or Long Glass—Creek. Sometimes, we shared with range horses and cattle. We all wore the same kind of bathing suits—white skin. When using the back house that was supplied with a Sears Roebuck catalog, we came out with print or pictures—possibly of a wagon, manure spreader, or other—on our rears. Girls went swimming by themselves in their flour sack underwear. Most of us boys had one pair of jeans (sold for a dollar) and one shirt. In summer, we didn’t wear underclothes or shoes; there was always a scarcity of clothing. Baths were taken once a week, in a metal tub of cold water. Before winter hit, all farmers went to town to stock up. Some bought as much as eight or ten one-hundred-pound sacks of flour. When our supplies ran out unexpectedly, Uncle Jim and I left early in the morning, before daylight, for town. No roads went as the crow flies. We walked most of the twenty-two miles behind the sled, so we wouldn’t freeze; and it seemed like it took forever to get there. In Poplar, we left Joker and Woodrow at a livery stable, and went for provisions. After loading up, Uncle Jim and I started our long trip home; it was nearly morning when we got back. I really slept well after all those hours in the freezing cold. When I was a little older and rode horseback to town in winter, I would stay overnight at the Gateway Hotel. What luxury, from being out in the cold weather so long. At the age of twelve, after I had spent about two years with Uncle Jim and Aunt Pansy, I pulled up stakes and went to work for Walter Dewitt, a bachelor who lived near the badlands. He didn’t have his own farm; he always rented from homesteaders and cultivated their fields. While Dewitt harvested wheat for other farmers, I lived alone in his shack, herding ranch stock off the property and away from his crops. I earned five dollars a week, and thought I was rich. He furnished me with Van Camp’s pork and beans (five cents a can), Pet milk, and a few eggs that the chickens laid. I saw Dewitt about once a week. One time, he told me my eating habits were too expensive, and said to cut down on beans and eat more eggs. When harvesting season ended, Walter moved, and rented another wheat farm, known as the Woods Farm. It was north of the badlands and closer to Poplar, a nice homestead with good buildings and land to till. He didn’t need me anymore, with the harvest over and winter coming, yet he let me go with him and work for room and board—since I had no place else. On the farm was a large pump house that Mr. Wood allowed to be used as a school; I went there for a little while. The teacher, Miss Sites, dated Walter a few times. A nice lady, she tried to help me, knowing that I was a loner. She said she’d been thinking of homesteading on the Indian Reservation and would like to take me along to help, but it never came about. During the winter, chores became fewer and fewer, so I left and started riding the grub line, until I could find a job. Altogether, I had worked several months for Dewitt. A lot of farmhands rode the line in winter, when jobs were few and far between. We’d go from ranch-to-ranch, have a meal or two, sometimes spend a night—or possibly several days; we never got turned down. If no one was at home, we went in and made something to eat, fed our horses, and went to bed; the next morning, we washed the dishes and left. I didn’t ride the grub line for long. I found work at Alexander’s farm, twelve miles south of Poplar. During long winters, it was rough working in the piercing cold—going hungry lots of times—and no place to lay down and call home. When I arrived at Alexander’s in the dead of winter, I had no money, and was wearing knee pants and a jacket (two sizes too big) that someone gave me. Jess Alexander’s family included a wife (who was very sick), three girls—Lela, Dolly, and Odessa—and one boy, Bud. All the children were near my age. I worked for room and board, starting my chores at 4:00 a.m.: feeding stock, cleaning the barn, and taking their children along with me to school. Afterward, I milked cows until 8:00 or 9:00 p.m., by lantern light. I drove Alexander’s team and sled seven miles to Grandview school, near my Uncle Bert Bilby’s homestead. I felt sorry for the horses; while we were in school, they had to stay out in the snow. Lots of times, they were covered with white when we got out. During long winter nights, we played cards and ate popcorn. The children and I slept upstairs in two adjoining rooms with a curtain between. It was very cold because the only stove was downstairs. One winter day, while walking down the road, wearing my only pair of torn and ragged jeans, I ran into Uncle Jim. I guess he felt sorry for me; he gave me a dollar to buy a new pair. I knew he couldn’t afford it, either. When spring arrived, school came to an end for me. I went on the payroll, earning thirty dollars per month, driving six horses abreast while walking behind a harrow. While working, I got acquainted with an old hermit, named Potter, who stopped two or three times for chow. He lived in the badlands, inside a long tunnel in the side of a hill; all he owned was a decaying wagon and two shabby horses. Potter mined what little coal he could from that hole, for a meager living. I don’t think he ever took a bath or shaved, and we all knew he never took off the blue handkerchief that was around his neck; the knot was always a greasy black. Potter was someone to remember, though. He had lots of stories to tell, and, true or not, I enjoyed listening. No one knows where he came from or what happened to him years later, but I like to think that his ghost patrols the badlands at night. One day, while I was working around the house, Mrs. Alexander’s illness got worse. I grabbed a horse and rode as fast as I could to Poplar, for the doctor. She died shortly after, leaving a young family. Not long after her death, I was sitting at the table, when Alexander came up from behind me without saying a word and hit me in the face with all his strength. I didn’t know why he punched me and wasn’t waiting around to find out. I packed up and left, with a smashed-in face. Months later in Poplar, I ran into Lela, and she told me her father was wrong; he found out that he had made a mistake. At the time, I didn’t ask her any questions, but I believed he thought Lela and I were getting together. I liked Lela very much, but that never happened. I thought he might have gotten the idea from his wife; she could have thought that about Lela and I, because she was bedridden all the time, since her mind was not too good. On leaving Alexander’s, I rode the grub line until finding work at Joe Flock’s farm. Flock, a bachelor homesteader from Germany, was a man of fair worth, for those days. His homestead was better than most: good dirt roads, nice buildings, and located on the main road to Poplar, which was ten miles away. Flock’s spinster sister, Mary, owned a farm across the road opposite his; Joe cultivated both wheat fields. As it was summer, I earned top wages; Joe paid me sixty dollars a month for plowing his and Mary’s fields, using eight head of horses. Very few hands made this much, but I put up with a lot. The food was terrible, not clean, or cooked well—and sleep was hard to get when Joe got drunk. One time, while eating Mary’s cooking, I cut into a gizzard; corn and wheat ran out all over my plate, and made me sick. Many times I went hungry, rather than eat her food—and I nearly starved. Joe was a rough-and-ready sort of guy, who liked his whiskey. He was a good man to stay away from when he’d been drinking. During harvest time, he’d go into Poplar with a wagonload of wheat and not come back for several days, or maybe a week. Joe would get boozed-up and look for a stray woman. Meanwhile, I’d keep things going at the farm, until he returned. Flock usually came home late at night; when I heard him, I’d slip away to find a safe place to sleep, where he couldn’t find me. Some of my other cousins worked for Joe, but not very long. Cousin Lionel did, until Joe almost scared him to death one night. Lionel never went back. Cousin Tobe—a tall, lanky, copper-colored boy—was too strong and tough for Joe; he was the only one that Joe wouldn’t bother. Occasionally, I rode over to Uncle Willy’s homestead to see Cousin Tobe. Tobe’s real name was Ross, but not many knew that. Lots of cowboys had nicknames, for some reason or other. Tobe’s brothers were Royce, called Nig; Cecil, known as Hem; George was called Buck; and Cousin Lionel was nicknamed Rusty. In northeast Montana, I was Bood, and in Canada—Bronk, named after a wild mustang. I once thought of changing it myself, to Montana. On one trip, I left Uncle Willy’s house late at night, riding June, my little bronc mare I’d just broken in. Crossing the prairie around 2:30 in the morning, June dumped me, with my foot caught in the stirrup. She dragged me a ways before my foot suddenly came loose. There was no way I could have gotten free, except through God. June left me ten miles out from nowhere. I managed to walk through the night and into the day; a man on horseback saw me, and gave me a ride to Joe Flock’s. A day or two later, someone showed up with my mare and saddle. While at Flock’s, the flu epidemic hit, killing people all over the territory. Joe never caught it; he said whiskey kept him from getting it. One couple that lived far away from any neighbors caught it; the man died in bed, and his wife was too weak to get out. When the man was found, nobody could tell how long he had been dead. Another farmer was found in his barn, dead; he shot himself in the head when he got sick. Before winter hit, I left Joe and Mary; I couldn’t eat their food anymore. I got so thin, the only thing holding my pants up were my knees. My feet stayed brown from walking in cow patties all day. I figured if I was going to work for room and board throughout the cold season, I’d be better off riding the grub line, if no jobs were attainable. World War I broke out, and all eligible young men were called to duty. I was turning fourteen, so was not old enough to join. The government talked of raising food for the war, so some well-known, rich businessmen started the Montana Farming Corporation (M.F.C.). They set up headquarters in a bank building in Poplar and leased government land. Thousands of acres, set aside for Indians, were rented by the M.F.C. at seven cents an acre. They built long bunkhouses, large chow halls, and bought lots of trucks, tractors, and equipment. I rode to the Indian reservation and got a job with M.F.C., the largest farm company I ever saw or heard of. The field I farmed was located about twenty miles from town. At supper or quitting time, a truck picked up the hired hands; when we spotted it, all machinery was immediately turned off in its tracks and everybody made a mad dash for the truck. The seven-mile strip I worked had seven Autman Taylor trailers. These were mammoth tractors, with steel wheels two feet wide and eight feet high; the back ones had spikes. Every tractor pulled sixteen plows. Each rig was handled by two men: an engineer and a plowman. M.F.C. paid a bonus for distance plowed. The engineer received ten cents, and the plowman, five cents, per mile of ground turned. This was a big mistake. The land was heavy sod, and had never been tilled before. This made work slow, so they plowed shallow to increase their mileage. While working there, an army of grasshoppers came through. It took all the farmhands to fight these destructive insects. We hauled sack after sack of poison bran and bananas, throwing it as we walked through the fields; the yield that year was very poor. After two or three months, winter arrived, ending work with M.F.C., which compelled me to look for a job and a place to sleep. I found work at Candee cattle ranch and farm, owned by Elmer Candee; his brother, Floyd, also had a ranch in the area. They were sheepmen from earlier days, but split up and went their separate ways, both becoming cattle and horse ranchers. Since it was winter, I earned five dollars a week—plus room and board—for feeding Elmer’s stock. I started my chores at 5:00 a.m. and worked until 9:00 p.m. When getting up early in the morning, all farmhands stayed away from the stove. This made it easier to endure the freezing cold conditions. I worked all day out in this weather (sometimes 20 below zero) with a team of horses and a hayrack, throwing piles of straw or hay off onto snow-covered ground. When I stopped to rest, if it was sunny, I’d doze on the hayrack. After a long, cold day’s work, I went into the cabin at night and sat as close to the fire as possible, usually falling asleep. There was no heat in the room where I slept, but I had plenty of blankets and a cowhide on top. In my spare time, I liked to walk in the snow after sundown, and follow my footprints on horseback the next day. Sometimes I saw several coyote tracks behind mine. They didn’t bother me, just curious, I guess. Christmas at Candee ranch was a normal workday. But that evening, the neighbors got their families together and drove to Candee school for a party. Everyone brought food, someone chopped a Christmas tree, and parents gave their children presents. I didn’t expect anything, so when my name was called, it surprised me. I went to the front, and was handed a small bag of candy with my name on it. I was very happy, and thankful that somebody thought of me. I never found out who put it on the tree, but I always remembered that Christmas. I stayed at Candee’s only a couple of months. Work slowed to a standstill, so I left for Uncle Willy’s ranch. After three or four days with his family, I headed for the badlands with Tobe, carrying a pick and shovel to dig coal. We walked about ten miles in freezing weather, finally coming upon an old, abandoned shack. Inside stood one straw-covered, wooden bunk. It looked good, so Tobe and I laid down to sleep. We were restless all night because of the cold, and almost froze to death. Next morning, we found out that the bunk had just a thin layer of hay; underneath was a block of ice. We learned our lesson, and never slept with straw again. We went on our way, and later discovered a small four-by-eight pigsty. After digging beneath it for more room, we moved in, but it was too cramped for standing. We placed boards across the four-foot width to keep from sleeping on the wet, dirt floor. We had one blanket between us to share. I don’t know where we got it, because neither one of us owned enough to equal one dollar. Also, we had very little to eat, some cans of pork and beans, and not much else. Following a month of unsuccessful mining, and with our food all but gone, Tobe left for home. I stayed—I had no place to go. The pig shack was mine, alone, with storms and cold winds blowing. Several days later, a farmer passing through the badlands—with his team of horses that were so skinny and pitiful, they could hardly stand—asked me if I wanted to walk ten miles behind the sled, to his home. He said he’d give me room and board for doing chores. I left with farmer Sam Roe, my last meal in the cold ground was a can of frozen Pet milk. Sam lived in an old cabin with his wife and two sons, Fat and Skinny, which was appropriate, and the only names I knew them by. Mrs. Roe was a good, Christian woman, but Sam didn’t believe in heaven or high water. I heard he became well educated in his younger days, and was friends with the man who built The Great Northern Railroad. Why or how Sam ended up in the Missouri River woods lowlands, I’ll never know. He made a poor living, doing odd jobs with his team of horses. Their sons were not too bad, for boys. Fat sometimes told his mother to go to hell. Skinny never talked like that, yet Fat always did more for her than Skinny did. When working outside in the cold, Fat always grabbed the one pair of threadbare gloves. Whereupon, Mrs. Roe would holler at him, “Give one glove to your brother!”. Three times each day we ate homemade white bread with white Karo syrup, and felt lucky; Sam’s animals had a lot less. The horses were slowly being eaten alive; they were so weak, they couldn’t fight off the magpies that were biting holes in their backs. Farmers said that when magpies did that to a living creature, it was near death, anyway. It hurt me to see them suffer; I loved animals. After one month with Sam, I left, and hired out to Nebinger, a retired printer who purchased a wheat farm. I took care of his place and stock for sixty dollars per month, at the age of fourteen. During this period, I went to Poplar’s rodeo and fair, which was held once each year. There was bronco busting, bull dogging, roping, and many more events related to ranch roundups. Tobe and his friend, Cecil Gidley, went with me; we had a good time, for three riders hard up for money. Late that night, we looked for lodging in town. Rooms were scarce because of the rodeo, but after searching awhile, we did find one at a boarding house. Inside was one big room, divided by curtains, to make smaller rooms; we got three cots together. Cecil and Tobe laid down. I wasn’t sleepy, and was feeling good, so I looked behind the curtain to see who was next to us. I saw a buck and squaw sleeping, and thought it was probably their first time away from their teepee on the prairies. I shouted, “What the hell these Indians doing in here!” Both jumped out of bed and ran for the street. In a little while, two Indian police came back with this frightened couple, who pointed at us, behind the curtain. Tobe and I fell asleep very quickly. Cecil was so scared, he couldn’t close his eyes; they were wide open, like a dead man’s. The police looked in, and said, “These guys are asleep; you must have been dreaming.” The Indians insisted, “No, no,” and couldn’t be convinced to go back to bed. They took off for their lone prairie home, I guess never again to sleep in a motel. Next morning—with Poplar’s rodeo over—we headed south, across the Missouri River to our old location. I believe that’s the last trip Cecil made with Tobe and me. The next year, I attended the rodeo—but this time to be in it. Again, Poplar was full of people. Indians came with their families, and set up tents inside the racetrack field. Buster (my little near-white horse) and I entered the race competition. Buster had spent most of his life running free on rangeland. He was caught once by a rancher—who tried to break him—but Buster came over backwards on him. He was considered a bad horse, and was turned loose to run wild again. The more I saw him, though, the stronger my desire was to have this charger. I caught him, became his owner, and broke him. Buster never lost one race in Poplar. He was the fastest horse around, but this time the contest was held on an oval track. I soon found out that Buster wasn’t broken in well enough for this. The race started with a large group of horses—too many for Buster; he left the dirt track and I lost control. He was running toward the inside area of the racecourse, where all the Indians camped. Buster went wild, jumping over and into tents, knocking them down. Buster jumped over one tent with a large squaw (weighing about three hundred pounds) sitting under the flap; he turned her upside-down. Two bucks tried to catch us, but I hit one on each side of me with my knees by accident. I finally got Buster stopped. Tobe’s father was the first to reach me. He hollered angrily, “You better get out of town. These Indians are looking for you.” Buster and I left in a hurry, and neither one of us raced in Poplar again. We did remain good pals until I broke our partnership. Some man offered to trade his Model T for him. I had never owned a car, so I traded (no driver’s license, tag, or insurance was needed). But I never forgot my rebellious friend. Uncle Jim and Aunt Pansy were starved out of their homestead, and rented a better farm near town. When they vacated, I left Nebinger, and moved into my uncle’s place to farm his fields. I lived alone all fall, getting ready to seed. I fixed the loft for storage and cleaned up the barn, which was partly dug into the ground and made with straw. I also bought seven horses to help for planting and harvesting in spring; one was a saddle horse for riding. Winter became rough. I kept fairly warm by using the little cook stove and potbelly heat stove, as long as I changed sitting positions from time-to-time. The only light I had was an old kerosene lamp, and on a few occasions, I ran out of oil. Lots of nights were too cold to sleep, some being way below zero. I could hear nails splitting all night. On windy nights, snow blew through even the smallest cracks; and some mornings I’d wake up shaking white off my blanket. Sometimes snow banks were piled so high, I had to dig my way out of the shack. When big storms hit, I was shut in for days, and lost contact with the outside world. Nights were long and lonesome, with nothing to do except listen to the coyotes; three or four sounded like fifty, but it was a very lonely cry. When darkness descended, I’d look up at the hills and see Nebinger’s light burning four miles away; he was my closest neighbor. I felt better, knowing there were others beside myself out there. A few months passed and times got worse, starving me out. I decided to go to Gary, Indiana, for the remainder of the winter; it would be my first time back, since leaving Uncle George. A rancher, shipping cattle to the Chicago stockyards, bought my passage in return for watching over his herd. I rode the caboose with the train crew, and looked in on the cattle when the train stopped. At stockyards along the way, they were unloaded for feeding; I checked to see that all got watered and fed. After arriving in Chicago, I made my way to Gary, where I saw my half-sister, Elizabeth, and Grandmother Coldron, who was old and poor. I liked to see her; she always made good food. On one of my visits, the doctor was there. I didn’t know why, since my grandmother seemed healthy, but I heard her tell him she didn’t have long to live. Doc looked at her for some time, and then said, “I believe you mean that.” She said, “Yes.” During my short stay in Gary, I worked at the Consumer Store as a stock boy for fifteen dollars a week, and paid my room and board out of that. When spring came, I left for Montana, with my grandmother’s words: “You’ll never see me again.” Back in Poplar, I went to Uncle Jim and asked him if he’d sell me his homestead. He said, “I thought you weren’t coming back,” and had sold the three hundred and twenty acres to my neighbor, Elmer Keller, for fifteen hundred dollars. I was very disappointed. I stayed at Uncle Willy’s ranch two or three days, then Tobe and I crossed the Missouri to Brockton, where we went to work for the M.F.C. cattle ranch, located fifteen miles east of their farming corporation. Mr. Factory was general manager over both M.F.C. projects, and Jim Helman was foreman of the ranch. Jim was in his seventies, and the biggest man I ever met. He always rode in a wagon because he was too large for riding horseback. Many years before, he traveled down the Missouri by boat, and married an Indian squaw. They raised a wonderful family of half-breed children, all beautiful, dark-skinned, and well educated. Jim did most of the cooking (made good squaw bread), and drove the wagon to town for supplies. One of my jobs was going with Jim, to help. During my first few days there, I received a letter saying my grandmother had died. Tobe became a rider; he always liked “cowboy-ing” and breaking broncs. His riding partner, Drew, was an old-time cowboy, who never did anything else in his life. They got along well together. While at M.F.C., I had two incidents concerning Indians. One almost got me killed, the other, almost married (not really). My pleasant event involved an Indian girl. Drew’s brother, a squaw man, had a beautiful thirteen-year old daughter. When I rode through Indian Territory for M.F.C. and passed by her cabin, she’d run out and yell, “Would you like to marry a squaw?” I never stopped to talk, as I was too bashful, and also remembered my mishap involving Buster. I didn’t want to get mixed up with Indians for a while. The other incident started with a story that had been going around for quite sometime, before I came to M.F.C., about an Indian named Moses. I didn’t know him, so I thought it was just a wild tale. The story goes: An Indian living two miles from Poplar died, and was laid on top of some apple crates. A rancher paid Moses to sit with the corpse until someone came to bury it. Moses, sitting alone, fell asleep—but was awakened when one of the crates gave way, and the dead Indian fell over. Moses jumped up, ran all the way to town, and into a restaurant where some of the boys knew what he was doing. Moses stuttered so badly that they couldn’t understand him, so they went out to see what had happened. Well, Moses came to work at M.F.C. while I was there, and one day I teased him about the story. He went wild--mad, like a bull-- started stuttering, and almost beat me up. Then I knew that it was true, and never said anymore about it, and for good reason. During M.F.C.’s existence, its farming corporation and cattle ranch, alike, lost revenue. The owners lost thousands of cattle and millions of dollars because they weren’t experienced in the cattle business. Tobe and Drew found great numbers of hides back in the hills, stuck down old wells by Indians that were stealing the cattle and killing them for food. A lot of cattle drowned in the Missouri River due to lack of trained ranch hands; the drovers couldn’t control herds from pushing one another in, while trying to drink. The government, nevertheless, continued to support M.F.C. because it was done for the war effort. Work ended for me when winter hit, as it did for many, so I packed up and changed residence. I moved in with Earl Blevins, a bachelor who lived with his mother and sister. They were good people and I enjoyed staying there. I used their home as my winter base, between riding the grub line and when lacking a place to bunk down. In early spring, I left M.F.C., and worked small farms around the area until restlessness set in. When I was sixteen, I filed for homestead. The normal age requirement was twenty-one, but having no parents, I was permitted to homestead as the head of the family. I homesteaded one hundred and sixty acres, twenty miles southeast of Poplar. I built a small shed and seeded the ground. However, I lost the land because of a mix-up with relatives. I bought a team of gray geldings and a wagon for a trip to Canada with two families (each having their own rig). They were going for the harvest, and to settle there. Barnes’ family included one boy and girl; the Cramers had no children. We crossed the Missouri at Poplar, and headed north across prairies, driving slowly during daylight hours. At dusk, we hobbled our horses and turned them loose to graze while we ate supper. Early each morning, we cooked and ate breakfast, then hooked the horses up, moving north again. This went on for two weeks, until we reached the borderline known as Muddy Custom Office, where we ran into complications. Horses had to be checked for diseases, and each man was required to have a certain amount of money and a homestead in Canada. Mr. Barnes and Mr. Cramer traveled by train to the land office and filed for home grounds they never saw; the rest of us camped at the line several days until they returned. I had loaned my money to both men, so that they had enough to pass customs; and I went through as Cramer’s son. Then we headed sixty miles north to the Providence of Saskatchewan, seeing many small lakes and millions of ducks, as we journeyed. Finally, we arrived at our destination and began harvesting fields; we did fairly well, until cold weather moved in. We hauled bundles of wheat day-after-day to the steam threshing machine. At night, I slept in a granary, and some mornings woke up having to knock snow off my blanket. There was a good flax crop until it got snowed under, ending our task. My toes were frozen, also. I departed for Montana, leaving my team and outfit to both families, who promised to send me money. I was left with seventy-five dollars for transportation and to get through the winter. I caught the Canadian Railways, which crossed the border at north and south Portal, then into Fargo, North Dakota. Then I rode the Great Northern to Poplar. I never did hear from either family; that taught me that not everyone is a friend. I saw Floyd Candee in town; he said his teeth were giving him trouble and wanted them pulled, but the closest dentist was at Minot, North Dakota. Floyd asked me if I would take care of his place and feed the stock, so he could go. Even in winter, it was difficult to leave ranch operations. I moved into his cabin for three weeks, attending the cattle and workhorses. When Floyd returned, no money changed hands. It was merely one neighbor helping another, although I did borrow his team and sled to deliver coal. I paid two dollars a ton, and hauled two tons per load the ten miles to Poplar; I charged five dollars each ton. Others were doing the same thing, and trading for groceries or clothes because people didn’t have the money. Since I needed cash, I stopped and worked what jobs I could find, riding the grub line in between. When spring began, I got work at the 14 Ranch, owned by several wealthy people-- one, an attorney for the Great Northern Railroad. None of them lived there, but they maintained a beautiful white house on the land, for visiting and checking operations. 14 Ranch possessed lots of acres for raising white-faced cattle and alfalfa hay. Foreman Jim Montgomery, a tall, slim con man, liked his booze and card games, and won most of the work hands’ money. His pretty thirteen-year old daughter played with snakes; she’d wrap them around her neck. The foreman before Montgomery was Sullivan, who, like most old cowboys, enjoyed his whiskey, too. I knew him well and liked him, as a man. He left 14 Ranch to become sheriff, but after taking office, he got caught stealing cattle from 14 Ranch and was sent to prison. The ranch hands lived in long bunkhouses, and, like other gangs living together, they had their share of fights. Once, a cowpuncher put a large snake in another man’s bunk. Minutes later, the sleepy fellow crawled in, and upon finding it, flew out of bed. After getting over his shock, he tried to kill the prankster. We couldn’t blame him much, but none of us wanted anyone killed, so we slowed him down. The grub hall—located next to our bunkhouse—served food on long, homemade tables with planks for seats. At one end of the table, two big pans were placed: one to scrape leavings in, and the other for dishes and utensils. This saved on kitchen work. The cook would call us to meals by hitting two pieces of metal against each other, creating ringing sounds. At that moment, look out!-- Everyone ran for the chow hall that was full of good food. At roundup time, when we branded stock, work was hard and hours were long. Range horses ran wild; the only time they had a rope on was during branding. Herds were named by their leader’s description: buckskin herd, pinto, sorrel, and so on. Usually, a stallion took charge, keeping the mares together. Most Montana ranches held roundup around the same time. Frequently, ranchers gathering their stock got other brands mixed in. If it happened to be a mare and her colt not marked, the rancher put whatever imprint the mare had, on her colt; this was the way of the West. One of the biggest ranches, 44, seared their horses’ left jaw with the number “44”. Another ranch, Key and Pen, crossed their symbol on the animals’ right thigh. After roundup, stockmen turned their horses loose to run free again on the open range, all brands mixing together. Whenever one was needed, or there was a buyer, ranchers cut out what they wanted from the herd. The seller made clear he no longer owned the stock by venting his brand, done by putting it usually below the registered brand-- like signing a deed. If a buyer didn’t turn horses out as range stock, and only used them for saddle or work, he didn’t need his brand on them, since everyone would know to whom they belonged. The United States Army bought thousands of horses, all approximately fifteen hands high and black. They used large draft horses for heavy loads, and lighter ones as saddle horses. During the summer, range stock was fat and pretty; but in winter months became skinny and weak from traveling through deep snows, searching for food and finding very little. They pawed thick snow to uncover a few sprigs of grass, and ate snow when thirsty. During the hard winters, many starved. Some also died in spring, when their heavy coats itched; they’d lay down to roll, and didn’t have the strength to get back up, leaving themselves vulnerable to coyotes. On cattle roundups, we herded cows into big corrals, where branding was done quickly. Working in two crews, the cowhands caught and threw calves down. While one man branded, another castrated the young bulls—which made them steers—in order to obtain the best meat. That was one of my jobs. “Seeds” were thrown in one pile, and a cut-off piece of each heifer’s ear, in another. When we finished, scraps were counted to tell how many cattle the ranch had. Some cowhands threw the seeds on the fire, cooking and then eating them. I tried some-- not too bad. Frequently, while shipping cattle to stockyards, different brands got mixed in. But ranchers sent them with their herd, anyway. Stockyards deducted freight for strays, and mailed a check to the rightful owner. He never knew who shipped his cows, but he received his profit. I also worked in 14 Ranch’s alfalfa fields, assigned to a five-foot-blade mowing machine, cutting hay. Behind me, farmhands raked alfalfa into piles for picking up and stacking. One day in the fields, I had a bad accident with my lively team and mowing outfit. While coming in for lunch alongside other workers, the bridle came off one of the horses. I lost control and my team took off, running as fast as they could, and preparing to jump over a wagon. That’s when I leaped off the mower; everything ended up in a big pile. For fun, some of us wranglers got together and rounded up several wild horses to break. On such a day, I had my most dangerous ride. On one bronc, my foot became tangled in the stirrup; I fell and was being dragged. I thought it was over for me, until a young rider—named Twister, a very good horseman—managed to get close enough to this raging animal and untangle me. In no other way could it have been done, except through an act of God. I worked nearly a year at 14 Ranch. I learned to do everything the old cowhands could do, and more than many, because I knew how to castrate. I was a full-fledged hand at seventeen, earning top wages of sixty dollars per month during the summer. I got restless though, and wanted to move away from Poplar, from relatives, and forget my past. I saw very little of my uncles and cousins over the years, since leaving. I became a loner. Twister and I saddled up and headed toward Miles City, a cow town, on the way to Butte. We rode across country as the crow flies, seeing only prairies and prairie dogs. Halfway to Miles, Twister and I came upon a dilapidated cabin, where an old man lived alone. First thing, he said: “Get off your horses and feed them, then come in.” We ate and stayed the night. The next morning we went on our way, passing an old, abandoned town, where there was nothing but fallen-down farm sheds. After three or four days of hard riding, we reached Miles City and hunted for jobs, since both of us were broke. Twister found work south of town, at a ranch near Powder River; I never saw him again. I milked cows on a dairy farm. While working there, I lost my horse. Someone left the fence gate open, and he vanished, leaving me on foot. After two months, I left by way of the rails, with thirty-eight cents in my pocket and a fifteen-gallon black hat. I stored my saddle at the old Antler Hotel and walked down to the railroad tracks a short distance from Miles station and waited. Lots of guys rode the rails because most jobs were seasonal and widely spaced; field hands had only a few months each year, before everything froze up. When one job was completed, they moved to another harvest area, their best transportation being rails. Some rode tops of passenger trains or coaches-- others, the cowcatcher. I preferred tops of passenger cars, and used many different railroads and trains to get where I wanted to go. When the train stopped at a town, I usually got off and worked two or three weeks, then was on my way. Career bums didn’t care which route the locomotive took; it could be decided by the flip of a coin. They weren’t going to work, anyway. If they found a good town to beg in, they stayed awhile. Most railroad towns had a “jungle”, where bums hung out. They cooked coffee—and whatever else they could get—in tin cans. Sometimes, as many as thirty bums were waiting in the woods to hop a train. When dicks (railroad detectives) caught hobos on trains, they put them in jail for the night. Finally, the Milwaukee (a long freight) came through. I ran alongside, jumping toward an open boxcar. Two young men, wearing fifteen-gallon hats, were standing in the door; one of them pulled me inside. They saw I had a gun, and were afraid to be with me if we got caught. I didn’t see anything wrong, because all cowboys on the range carried pistols. We rode until the train slowed down for Glendive. Dicks began checking for rail-riders, so I jumped off on the business side of the tracks and ran close alongside the train, keeping out of sight. While running, I looked across the street and saw a sign: “Rooms upstairs”. I ran up, found an empty room, and fell asleep. My traveling companions were captured, and spent the night in jail. Glendive was building a new station, so I went to work there, but only for two weeks. That was just time enough to make a few bucks. Then, my two friends and I caught a freight for Butte. After many miles of riding, we arrived there and jumped off in the section known as Cabbage Patch. My first glimpse of Butte was of a woman beating up some man in the middle of the street. The three of us went to a restaurant for coffee, and met some girls, who thought we were with the show in town because of our big cowboy hats. We played along, until I found out my companions were trying to con the girls out of their money. I left, and lost them for good. Butte, known as the richest hill in the world, had mountains all around, being mined. Most of the town was built over the mines. Butte was made up of gambling houses, bars, hotels of prostitution, and lots of boarding houses. Barbershops were run by women. While getting a haircut, one could make a date. More bachelors and loose women were in town, than were families. I walked to the main employment office for mines, to get a rustling card. Because I was seventeen—which was too young—I added two or three years to my age, and received a card. It was necessary to have this identification before working. While employed, a worker’s rustling card went back to the office until it was needed again. Foreman Jones, at the North Butte Mining Company, hired me and took me to Olson, the shift boss. Olson told Patty, a big Irishman, “Take this kid down and make a miner out of him.” First time being lowered into the shaft felt very unpleasant. We dropped like a bucket thrown down a well. I would have given anything to get up. I didn’t dare spit, for fear I’d spit my heart out. I started as “mucker”, which was a rookie’s first job toward becoming a miner. I worked under miners on the four-hundredfoot level, where it was extremely cold and dark, shoveling ore into chutes. Miners wore dog tags around their necks when in the hole, in case of an accident. Companies provided lockers for changing clothes before descending and after ascending. There were also hot showers. Work garments were called “turkey clothes”. Hardhats with carbon lights (or lights having sharp, metal points similar to ice picks for sticking into timber) were furnished. Mines consisted of different levels, two hundred feet, four hundred, six hundred, eight hundred, one thousand, fifteen hundred, and on; certain levels maintained various storerooms for equipment, tools, and dynamite. Transferring men to their work areas was done fast because there were so many to get down. Workers crowded into three cages that were stacked, one on top of the other, and lowered with a large cable. The bottom cage was boarded first, and then dropped for the second cage, then the third. When these were filled, one man in each cage pushed his foot against the door to close it. The engineer, who lowered the passengers, was hundreds of feet from the mouth of the mine and couldn’t see the cages. He earned big money, since the miners’ lives were in his hands. He had to be sober and reliable. He was always watched closely, on and off-duty. The loader gave the engineer signals, by pulling an electric cord a certain number of times for each station. Every station had a signalman. Miners descended straight down the shaft, hundreds of feet per second. Where the miners disembarked, the stations were lit up. But miners went a half-mile or more in branches, spreading out in all directions to reach their locations, with very little light. Removing ore from the mines started with muckers, shoveling ore from different levels into chutes, which loaded into electric rail cars on the main levels. Then rails transported ore to skips—large metal containers—which pulled it topside. Only after miners were dropped for the day could ore be raised, for skips replaced the cages. Once it reached the top, ore was dumped in overhead chutes and loaded into railroad cars. Trains carried it to Anaconda, thirty miles away. Anaconda Refinery was known as the largest smokestack in the world. Mr. Olson was very good to me something I wasn’t used to. He kept pushing me, so I’d advance quickly to miner. I did, and in a short time my job changed to timbering up overheads in stops. Stops were about four feet square, and, like main roads, drifted and turned, following a vein of ore. One gang drilled rock ahead of me, pursuing the vein and making room. Then muckers shoveled ore and rock into chutes, while I got another four-by-four ready for timbering. I worked many different levels. Motormen and switchmen, deep down, received good pay because of the dangerous conditions; raise miners (as a rule) made more, too, because of the hazardous work. Raises were like manholes, except dug from lower levels to higher ones. Later, I learned how to use dynamite. I became good at that, and was promoted to shooting and blasting. I mastered placing explosives, just the right way, for maximum effect; I used less sticks, so I had extra for further blasting, which meant additional money for me. I made more money than ever before. I bought my first good clothes, and plenty of them. I also had my picture taken. I bunked at a boardinghouse for miners, where they fixed lunch to take and cooked evening supper. The landlord collected our paychecks, taking what we owed and giving us the remainder. Most miners didn’t work steadily, and were usually broke from payday-to-payday. Many heavy drinkers and gamblers stayed drunk and wouldn’t work, until their money ran out. Most of the time they were looking for jobs; if they had more than five in one month, the rustling office warned them about losing their card. I thought I had to be like my fellow workers, so coming out of the hole after the midnight shift, I went into a bar and drank one pint of liquor before going to bed. I also lost lots of money gambling. It didn’t take long, though, to see this wasn’t doing me any good, so I quit. Miners supported many women; there wasn’t a building that didn’t have them in it. If a miner’s door wasn’t locked, the women would be in his room, regardless of an invitation. They never got much of my money. I liked pretty girls, but seldom dated; I was afraid to get tied down. I liked my freedom to move on anytime I pleased, and knew that girls would be around for a long time. Mine companies wanted bars, gambling, and ladies; they kept men broke, happy, and working. Miners who didn’t kill themselves with vice, usually died from dreaded tuberculosis. There was no real cure, and not much care was given to those who had it. Before my arrival in North Butte, there was a fire that was one of the great mine disasters of the era; between three and four hundred were killed by smoke. Some say many could have been saved, if the authorities had let the fire burn timbers in the shafts. Instead, they poured water down, putting the timber fire out and driving smoke farther below, suffocating the miners. Following the catastrophe, tunnels were dug to other mines. The incident was not easily forgotten; fires broke out in the minds of men, who were working far below the surface. While earning plenty of money, I got too big for my britches, craving more, so I quit Olsen and hired on to another foreman. Olsen disliked that; he wanted me to enroll at mine college. I labored one mile under, where air was forced down through big, sack pipes. It was so hot, like an oven. I could only work twenty minutes of each hour, and was always covered in sweat and copper water that seeped from the walls and ground. I was sorry I left Olsen, but it was too late. I told the new boss I couldn’t do a good job, because of the heat—and decided to quit. He said, “You’re doing all right,” and talked me into staying. After one year in the mines, I figured I was long enough in any one place. Besides, I was eager to get out of the hole. I walked to the train station and was waiting for a ride when I met miner Joe Burden. We noticed the Northern Pacific Railway was employing men for rail work; we got an idea and hired on. Joe and I shipped out as new workers, with free passage on a passenger train that was heading toward our job destination. Upon arriving, we disappeared and found work on a wheat farm. Joe didn’t like harvesting, and wanted to go back to Butte’s mines. We did, and roomed together at 128 West Park Street, and later at 136 Main Street. He was a good miner and made big money, but gambled it all away. Before long, I caught roaming fever again and hopped a freight going west. When the train stopped in Drummond, I jumped off and milled around the station like several other guys. A man came up to me, after loading his wool products on boxcars, and said he could get me a job at Dooley Sheep Ranch—I went. Two brothers, up in years, owned the spread inherited from their parents; neither ever married. Both drove big cars—one, a Franklin. Wherever they went, the back seat was loaded full of sheepdogs. The hired hands said Dooley’s father was shot and killed years ago by a horse thief, having the same last name, but was no relation. Their mother said she would marry the man who killed her husband’s murderer. A man did, and she kept her promise, but didn’t live with him very long. He was well taken care of, though, and even received money from the sheriff’s office because of the bounty on the thief. I worked, making alfalfa hay; irrigating, cutting, raking in piles, and stacking it up for winter feed. I slept in a bunkhouse, located near a mountain creek, running with icy waters. Work hands washed and drank there. One Sunday, several guys were trying to break a bronc. I uttered some remark, and one of them yelled back something that angered me. I said, “Where I come from, we’d call him a gentle horse.” They hollered, “Come on and ride him, then,” thinking I wasn’t a rider. The horse was in Dooley’s large corral, made of poles. There was one pole for the gate, which went up when opened. A couple of cowboys saddled the wild bronc for me. I said, “Take his bridle off. Where I come from, we don’t use it.” I was never safe; that bronc gave all I could take. When he quit bucking and started running, he hit the big gate, flinging it open. I quickly reached up, grabbed hold of the pole, and jerked myself up. Outside the corral were clusters of trees; there could have been trouble if I had stayed on. The hands all came over and told me it was a good ride. I boasted, “Where I come from, we wouldn’t call him a bad horse.” The truth is, I had had all I could handle and all I wanted. Dooley Ranch asked me to ride for them at Deer Lodge’s big riding contest, held on July 4th. But I had no riding equipment, so I didn’t enter. After one short summer there, I grew thirsty for excitement and headed back to Butte. I labored in the mines two or three months, then left, riding on top of a Northern Pacific passenger train. When we stopped at Ryder, North Dakota, the conductor saw my shadow on the ground and came running and yelling at me to get off, which I did. Stranded, with nothing except the clothes on my back, I began job hunting. I met Mr. Rose, the owner of two farms, two threshers, and a home in Groton, South Dakota. His wife, four sons, and two daughters toiled hard; the children, regardless of age, turned their money over to their parents. Rose needed help harvesting the fields, so he took me on. They were a good, German family; I got along with them all. When the season ended, ushering in cold weather, I told two of Rose’s sons—Elvin and Melvin—that I was going to Chicago. I would stop in Poplar for a short stay, and would write them when I got settled, I assured them. Mr. Rose asked me if I’d drive him home to Groton in his car, which I did, then bought a ticket to Poplar. I surprised my relatives-- they thought I was dead. One of my uncles said the rumor spread because no one had seen or heard from me since I left. I knew no one really cared, anyway-- as it was for most orphans, nobody was concerned about when and where I went. One evening, as cousin Tobe, his friend, and I sat around talking, I persuaded them to go to Butte and work in the mines. We hitched a ride on the Great Northern, until getting sidetracked in Laural, known as a tough town for hobos that rode without tickets. During the night, it became mighty cold, so we looked for some place to keep warm. I found an unlocked boxcar, but inside were lots of tramps, wrapped in heavy shipping papers. They looked warm and comfortable, while we were cold and miserable. I let out a holler, “Get out of there, you bums!” and darted behind the car. They all jumped out and ran in different directions, thinking it was bulls (railroad dicks). While looking things over, a brakeman came along and glanced in the boxcar. I thought it was Tobe, and heaved him in; I really scared the guy. I realized my mistake and took off. I had no wings, but my legs moved really fast. I left Tobe to face him, and do the explaining. The brakeman was too shocked to do anything, so we had the whole boxcar to ourselves, with wrapping paper to spare. We slept warm and sound. Next morning, the Milwaukee, a long passenger train, filled and pulled out. We leapt on as it began moving away from town. We heard that a lot of these towns were known for their tough railroad dicks. Henceforth, at night, when the Milwaukee slowed down to stop, we’d jump off and run alongside, dodging any bulls. At one station, Tobe and I jumped back on in the front; we didn’t see our friend, and could hear the dicks putting bums off at the rear; we figured he was thrown off. Many miles and lots of stations later, the train slowed for Harlotown; it was early morning and still dark. Tobe and I leaped off to avoid bulls. Looking back, we saw a man way down the track, walking fast. Assuming it was a bull, we took off running. Then he commenced in hot pursuit. We ran until we could go no more, and just sat down. The guy caught up to us and we didn’t know whether to be mad or glad; it was our friend. He had gotten off at the back and seen us, then attempted to catch up. When we started running, he thought that someone was behind him, chasing us all. We rested a few minutes, then walked up the track and jumped into another boxcar as the train began moving. Several bums, intoxicated from drinking sternotype cooking fuel, vaulted in after us. These were called “canned heaters”. The west was full of these men, who were crazy from years of absorbing canned heat. Nearing Deer Lodge, one of them tried to throw me out; two or three times, this bum had me at the edge while the train was moving fast. Finally, near the opening, I pulled around his side, got in front of him, and shoved him out. He rolled—tail-end-over-applecart—bleeding, scratched, and full of canned heat. As we arrived in Deer Lodge, a small number of bulls were waiting. Seeing the hobo down the track, they grabbed him and left. I guess they put him in jail for a day or two; bulls didn’t like “canned heaters”. We continued on until the train slowed for Butte, where we jumped off and walked to the mine office for rustling cards. First day down in the mine, Tobe and his companion couldn’t wait to get up after dropping only a half-mile. Next morning, Tobe and his friend departed with a railroad gang that was laying track two hundred miles away; I stayed. Two weeks later, I received a letter from Tobe, telling me where he was. I quit the mine and caught a freight that was headed near his location. Upon arriving, I ambled up the track until I found him. Tobe quit that night, and we headed for Kansas—the great wheat country—leaving his friend at the railroad. We hitched a freight to Cheyenne, Wyoming, and went to a cheap hotel. We slept all night and into the next evening, until the landlady burst in around 6:00 p.m. and yelled, “Get out, you bums!” We didn’t know we had slept all day. We hopped a freight that stopped in Denver, Colorado, where Tobe wanted us to join the Navy. I said “no”, so we continued on to Pueblo in a boxcar, loaded with wooden poles. The weather was very cold. I fell asleep awhile and woke up scared; I couldn’t open my eyes. But soon I could; they were just matted shut. From Pueblo, we traveled to Kansas, and hired out to a farmer in Colby. We worked all day and slept in his barn at night. Upon collecting our wages, we left for Wichita. The town was under water, so we got jobs cleaning stockyards as the floodwaters receded. We were only there long enough to make a few dollars, and then headed toward the Kansas wheat fields. Tobe and I labored many hard days, harvesting wheat in several small towns throughout Kansas. Two-thirds through harvest season, we split up. Tobe took on a partner and kept the old Model T we bought, and I moved on with two older men, who were supposed to be harvest hands. While camping beside a road, the sheriff came up and asked a lot of questions; it seemed like he knew about these two. They told him I was a friend, but I learned they “harvested” harvest workers instead of fields. They brought out the old shell game. I had never heard of it before, so they conned me out of my money and ditched me at a crossroads town. Harvest was over and I was broke. I wrote Aunt Stella in Indiana, asking for money so I could buy a ticket to Gary. I remained in Kansas two or three more weeks, doing chores in exchange for sleeping in an old man’s barn. When the letter came, I purchased a ticket to Chicago and then caught a ride to Gary. If you enjoyed this much, look for the book on Amazon: Title: "Orphan Boy" by R. J. Milne, Jr.

|

|